Concurrent diagnosis of rheumatic mitral stenosis and aortoarteritis:

A rare combination

Suneil Kumar Aggarwal, V Ramnath Iyer, Vijay Sai, Jitendra Mishra

Department of Cardiology,Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Medical Sciences

Prashantigram, Andhra Pradesh,India

|

|

Introduction

Aortoarteritis and mitral stenosis are individually more common conditions in India than most other countries. However, we are not aware of any reports in the literature of diagnosis and treatment of the two conditions in the same patient. Our patient was initially diagnosed with mitral stenosis, and only subsequently found to have aortoarteritis during work up for a planned balloon mitral valvotomy.

Case Report

A 21-year-old lady of rural origin presented to our department in July 2004 with a 4-month history of shortness of breath on exertion, and a recent echocardiographic diagnosis of mitral stenosis by another institute. At the first out-patient visit she was found to have a urinary tract infection with E. coli, and so the proposed balloon mitral valvotomy was deferred. Soon after that she was diagnosed with biopsy-proven tuberculous lymphadenitis and had 6 months of anti-mycobacterial medication. She finally came back to our institute for the treatment of her mitral stenosis in early 2006.

At that time, her shortness of breath had worsened, with occasional episodes of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, palpitations and a general feeling of tiredness. On examination, her pulse was 96 beats per minute and blood pressure was 156/90 mmHg. Cardiovascular examination revealed a left parasternal heave, a tapping apex, with loud and palpable 1st and 2nd heart sounds as well as an opening snap. There was a grade 3 mid-diastolic murmur at the apex – all findings consistent with her primary diagnosis of mitral stenosis.

ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with right axis deviation, right ventricular hypertrophy with strain and biatrial enlargement. The chest X-ray showed signs of pulmonary venous hypertension. Routine blood investigations were within normal limits.

Her transthoracic echocardiogram showed a pliable, non-calcific mitral valve with a typical rheumatic appearance. The mitral valve area was 0.7 cm2 with gradients of 31/22 mmHg. There was trivial mitral and tricuspid regurgitation. The estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 100 mmHg. However, routine pulse wave doppler of the abdominal aorta showed continuous flow. There was an apparent narrowing at the lower end of the thoracic aorta on colour doppler with a gradient of 65/9 mmHg.

Since a balloon mitral valvotomy was planned a trans-oesophageal echocardiogram was done, which showed the absence of clot in the left atrium and atrial appendage. Posterior rotation of the probe allowed closer examination of the descending aorta, which confirmed a narrowing at the junction of the thoracic and abdominal aortae. The irregularity of this narrowing was suggestive of type IV aortoarteritis, based on a newer system of classification of this condition.1

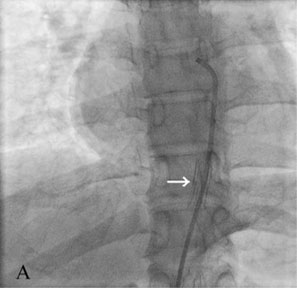

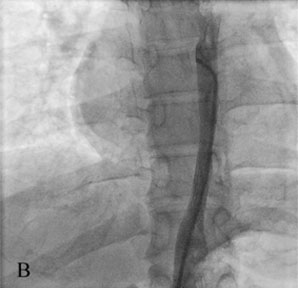

Treatment was carried out at two separate catheterisations. Being the distal lesion, the aortic narrowing was dilated first. This was to prevent increased pressure on the previously unexposed left ventricle, had the mitral stenosis been treated first and the aortic narrowing remained. The stenosed aortic segment was visualised on angiography (Fig. 1). There were no lesions seen in any other arteries. Pre-dilatation pressures were measured, and found to be 148/88 mmHg in the thoracic aorta and 77/63 mmHg in the abdominal aorta (distal to the narrowing), with the peak gradient calculated as 73 mmHg. The lesion was successfully stented with a 12 by 20 mm self-expanding Symphony nitinol-coated stent (Medi-tech, Boston Scientific Corp., Natick, MA) (Fig. 2A). This led to an improvement in flow through the aorta (Fig. 2B). Post-stenting pressures almost equalised in the ascending (129/81 mmHg) and descending aorta (119/80 mmHg).

Correspondence: Suneil Kumar Aggarwal, Department of Cardiology,Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Medical Sciences

Prashantigram, Andhra Pradesh,India

E-mail : suneilaggarwal@doctors.net.uk

|

|

||

| Figure 1. Aortogram showing tight narrowing of the abdominal aorta proximal to the origin of the renal arteries. | ||

|

||

| Figures 2 Post aortic stenting images: (A) prior to dye injection (white arrow points to stent) and (B) after dye injection. | ||

A second cardiac catheterisation was performed 2 days later for the balloon mitral valvotomy (BMV). The mitral valve was dilated to 24 mm using a 23-26 mm Accura balloon (Vascular Concepts Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, balloon size based on height of 151cm), leading to a fall in left atrial pressure from 34 to 15 mmHg.

Discussion

From our literature search, we believe this is the first case of aortoarteritis being concurrently diagnosed ante-mortem with rheumatic mitral stenosis, even though they have been found together at post-mortem before.2 Although of worldwide distribution, aortoarteritis is comparatively more prevalent in the Indian population than in most countries. In India it most commonly affects the abdominal aorta and renal arteries, in comparison to the originally diagnosed patients of Japanese origin.3 Rheumatic heart disease is estimated to be present in 1.4 million people in India with mitral stenosis being the most common valvular disease in women in India.4 Considering the relative prevalence of the two conditions, it may be surprising such a case has not been discovered before. The most likely explanation is that the aortoarteritis had not been detected clinically, since for many patients like in our report, it may not cause symptoms, even though it may be causing hypertension. Another interesting feature of the report is the occurrence of aortoarteritis in a patient recently treated for tuberculosis, as there is data suggesting an aetiological link between the two conditions.5

Our report highlights the importance of thorough echocardiography in a patient, regardless of the underlying aetiology of their principal disease. This patient had no history suggestive of either active aortoarteritis or lower limb circulatory deficiency. There was however a relatively high upper limb blood pressure for a patient with mitral stenosis. Of course, thorough examination of the lower limb pulses would also have raised the possibility of the diagnosis prior to echocardiography. Retrospectively they were examined and found to be weak.

The treatment in this case was straightforward. Stenting for aortoarteritis is well established,6 while balloon mitral valvotomy is the most commonly performed percutaneous intervention in our institute. It is possible that the two procedures could have been carried out at the same time, although we felt the potential bleeding risks during septal puncture while using heparin (needed for the aortic stenting) were not worth taking. One possibility would be to perform the septal puncture, then stent the aorta quickly, followed by the BMV. This could be considered if such a case was to arise again.

References

- Moriwaki R, Noda M, Yajima M, Sharma BK, Numano F. (1997) Clinical manifestations of Takayasu arteritis in India and Japan – new classification of angiographic findings. Angiology 48: 369-79

- Kinare SG. (1994) Cardiac lesions in non-specific aorto-arteritis. An autopsy study. Indian Heart J 46: 65-9

- Yajima M, Numano F, Park YB, Sagar S. (1994) Comparative studies of patients with Takayasu arteritis in Japan, Korea and India - comparison of clinical manifestations, angiography, and HLA-B antigen. Jpn Circ J 58: 9-14

- Grover A, Vijayvergiya R, Thingam ST. (2002) Burden of rheumatic and congenital heart disease in India: lowest estimate based on the 2001 census. Indian Heart J 54: 104–107

- Modi G, Modi M. (2000) Cold agglutinins and cryoglobulins in a patient with acute aortoarteritis (Takayasu's disease) and tuberculous lymphadenitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 39: 337-8

- Sharma S, Bahl VK, Saxena A, Kothari SS, Talwar KK, Rajani M. (1999) Stenosis in the aorta caused by non-specific aortitis: results of treatment by percutaneous stent placement. Clin Radiol 54: 46-50

|