“Antiplatelet Drug Resistance in Patients with Recurrent Acute

Coronary Syndrome Undergoing Conservative Management”

Santanu Guha.(Professor and Head), Soura Mookerjee, Associate Professor, Pradipta Guha. (Post-Graduate Trainee), Partha Sardar. (Post-Graduate Trainee), Suryyani Deb SRF, Puspita DasRoy JRF, Rathindranath Karmakar. Senior Resident,

Siddhartha Mani. (Post-Graduate Trainee), Hema M B . Senior Resident, Santasil Pyne Asst Professor, Prantar Chakraborti. Asst Professor,0 P. K.Deb, Chief Cardiologist, Prabir Lahiri, Scientist, Utpal Chaudhuri, Director.

Department of Cardiology, Medical College, Kolkata, India,**Department of Medicine, Medical College, Kolkata, India

*** Institute of Hematology & Transfusion Medicine, Medical College, Kolkata, India, ****Department of Biochemistry, Calcutta University, *****Department of Cardiology, ESI Hospital, Kolkata

|

|

INTRODUCTION Aspirin is a well-established medication in the treatment of atherothrombotic vascular disease. However, despite taking aspirin a substantial number of patients experience recurrent ischemic episodes1,2. There are various laboratory techniques to evaluate the effectiveness of aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Approximately one in eight high-risk patients (12.9%) will experience a recurrent atherothrombotic vascular event in the subsequent two years despite taking aspirin 2. Some other studies have also confirmed that patients found to be aspirin-resistant by laboratory methods are at an increased risk of major cardiovascular events6, 7, 8, 9. Increasing the dose of aspirin is one possible solution to overcome resistance but meta-analysis suggests that a dose in excess of 325 mg per day carries no therapeutic advantage but does have an increased risk of side-effects10. Clopidogrel in combination with aspirin is the currently recommended standard of care for patients with ACS11. However resistance to clopidogrel is also not unheard of12. Recurrent ischemic episodes still continue to haunt physicians and cardiologists alike. In the present study, we tried to ascertain any correlation between recurrent ischemic events and resistance to aspirin and clopidogrel and also to assess the prevalence of other conventional risk factors. |

Material and Methods

Study group

We prospectively included 210 patients between July 2008 and May 2009 after obtaining an informed written consent. The patients were recruited from Cardiology ward and ICCU of Medical College, Kolkata. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee.

Inclusion criteria were:

| a) | Patients with acute coronary syndrome including both ST elevated acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) and Non-ST elevated acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). |

| b) | Patients who received both aspirin and clopidogrel (325 mg loading dose and 150 mg of maintenance dose of aspirin and 300 mg loading dose and 75 mg maintenance dose of clopidogrel). |

Exclusion criteria were: |

|

| a) | Concurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| b) | Family or personal history of bleeding disorder |

| c) | Patients with platelet count<150X103/L or >450 x103/ML. |

West Bengal, INDIA

E-mail: guhas55@hotmail.com, Telephone: 09831016367

|

Blood samples

Blood samples for platelet function assays were collected from an antecubital vein using a 21-gauge needle 2 to 4 hours after antiplatelet therapy intake. The first 2 to 4 mL of blood was discarded to avoid spontaneous platelet activation. Blood samples were collected in 3.2% citrated plasma.

Platelet Function Analysis

Platelet aggregometric study was done at IHTM, Medical College, Kolkata. Platelet aggregation with 10mM epinephrine, 2mg/ml collagen and 10mM ADP was performed with light transmittance aggregometry in all patients according to a standard protocol.3 Briefly, platelet rich plasma (PRP) was obtained after centrifuging blood at 200g for 15 min. Platelet poor plasma (PPP) served as an appropriate blank and it was obtained by centrifugation of blood at 1500g for 15 min. Platelet aggregation induced by Epinephrine, ADP and Collagen was measured by standard aggregometric technique based on optical density in an aggregometer (Chrono-Log, USA, Model 530BS). Platelet aggregation was defined as the difference in light transmission measured in PPP and PRP. Agonist (epinephrine, ADP, collagen) induced aggregation was studied at least 7th day after initiation of anti-platelet therapy.

Definition of low response

Patients with ≥50% aggregation with collagen (2 mg/ml) but ≤50% aggregation with ADP (10µM) were labeled as aspirin resistant and ≥50% aggregation with ADP (10µM) but ≤50% aggregation with collagen (2 mg/ml) were labeled as resistant to clopidogrel. Dual resistance was defined as ≥50% aggregation with both collagen (2 mg/ml) and ADP (10µM), as published in recent literatures and according to the recommendation of ACC/AHA 2005 guideline13.

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean+/-SD. Variables have been analyzed for a normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Differences between groups were assessed with the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Unpaired t tests were used for comparison of normally distributed continuous variables between the 2 groups. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS v17.0 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago).

Results

Recurrent episodes of ACS were more common in relatively younger age groups in comparison to patients with first attack of ACS (table 1). No difference was found with respect to sex, Body Mass index (BMI), use of medication like statins, ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, and Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF). Total cholesterol and LDL were higher in the recurrent group. (Table1).

Table 1 Demographics of the Study Population

Variable |

Recurrent |

First attack |

P |

Age, years (+/- SD) |

54.6 ±10.9 |

58.5 ±12.2 |

0.065 |

BMI(Kg/m2) |

24.3±4.2 |

23.9±2.8 |

0.465 |

Male Gender, n (%) |

32(80% ) |

122( 72% ) |

0.327 |

Statin usage |

40(100 %) |

170(100 %) |

|

ACE inhibitors/AT receptor Blockers |

34(85%) |

152(89.4%) |

0.415 |

Beta blockers |

29(72.5%) |

122(71.7%) |

0.725 |

Calcium channel blockers |

9(12.5%) |

38(12.5%) |

1.000 |

LVEF(%) |

46.6 ± 7.4 |

48.3 ± 5.4 |

0.098 |

Total cholesterol(mg/dl) |

218 ± 56 |

194 ± 62 |

0.026 |

HDL(mg/dl) |

34± 19 |

39± 10 |

0.021 |

LDL(mg/dl) |

145 ± 45 |

133 ± 39 |

0.091 |

TG(mg/dl) |

210 ± 98 |

187 ± 110 |

0.226 |

|

Table 2 : Prevalence of conventional risk factors and its correlation with aspirin, clopidogrel and dual drug resistance

Risk factors |

No.of pt. |

Aspirin resistance (%) |

Clopidogrel resistance |

Dual Drug resistance |

DIABETES |

Recurrent |

10 (41.6) |

23 (95.8) |

10 (41.6) |

|

First attack |

26 (35.6) |

41 (56.2) |

18 (24.3) |

HTN |

Recurrent |

12 (40) |

28 (93.3) |

12 (40) |

|

First attack |

36 (37.5) |

48 (50) |

20 (20.8) |

SMOKER |

Recurrent |

8 (29.6) |

21 (77.8) |

9 (30.8) |

|

First attack |

24 (30) |

32 (40) |

12 (15) |

ELEVATED LDL |

Recurrent |

12 (41.4) |

23 (79.3) |

12 (37.5) |

|

First attack |

42 (36.2) |

61 (52.6) |

24 (20.6) |

FAMILY HISTORY |

Recurrent |

4 (50) |

6 (75) |

4 (50) |

|

First attack |

5 (41.7) |

9 (75) |

3 (25) |

|

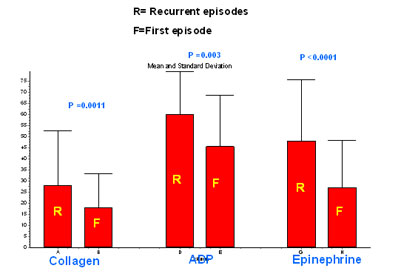

Figure 1: Mean aggregation pattern in response to agonists in patients with first episode of ACS and recurrent ACS. |

|

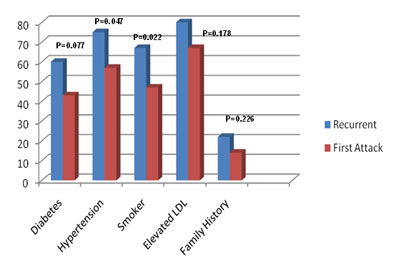

Figure2: Prevalence of conventional risk factor in patients with first episode of ACS and recurrent episode of ACS |

|

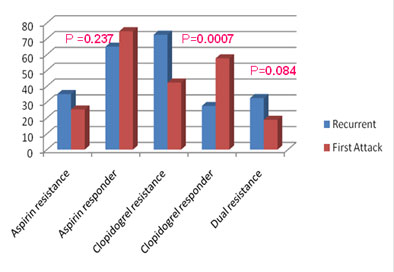

Figure 3: Prevalence of aspirin, clopidogrel and dual drug resistance in patients with first episode of ACS and recurrent ACS. |

Mean platelet aggregation with collagen, ADP and epinephrine in group A (n= 40) were 28.2±24.5%, 60.0±19.4% and 48.2±27.7% respectively (table2). The corresponding figures in group B (n= 170) were 18.1±15.3%, 45.6±23.2% and 27.0±21.4% respectively (Figure 1). Above data suggests a higher platelet aggregation in recurrent ACS patients as compared to first episode of ACS irrespective of the agonist used.

Risk factors were more prevalent in group A. Risk factors mainly observed in our study were diabetes (60% in Group A, 43% in group B), hypertension (75% in Group A, 56.4% in group B), smoking (67.5% in Group A, 47% in group B), elevated LDL (80% in Group A, 68.2% in group B), and positive family history (22.5% in Group A, 14.1% in group B) (Figure 2).

In Group A, 35% of patients were aspirin resistant, 72.5% of patients were clopidogrel resistant, and 32.5% of patients were resistant to both the drugs. (Figure 3).

In Group B, 25.3% of patients were aspirin resistant, 42.3% of patients were clopidogrel resistant, and 18.8% of patients were dual drug resistant (Figure 3).

The presence of conventional risk factors like diabetes, hypertension and elevated LDL in patients with recurrent ACS was found to confer increased resistance to antiplatelet therapy. (Table 2).

Discussion:

Aspirin and clopidogrel resistance are terms that have entered the lexicon of physicians and cardiologists alike without much evidence to causally associate such resistance with recurrent ischemic episodes. Risk of recurrent vascular events among patients who take aspirin is estimated to be 8 -18 % over two years14,15. Mechanism of aspirin resistance is multifactorial including extrinsic mechanisms and intrinsic mechanisms16, 17. Clopidogrel is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes 3A4 and 1A2. Polymorphism in the ADP receptor or differences in the post receptor signaling pathway may be responsible for clopidogrel resistance6,18.

Although a causal relationship cannot be established, some studies have highlighted the role of aspirin resistance in the incidence of recurrent vascular events7,8,19,20.

|

Gum et al designed a study to determine if aspirin resistance is associated with clinical events which included 326 stable cardiovascular patients on aspirin (325 mg/day for ≥7 days) and no other antiplatelet agents. The patients were followed up for 679 ±185 days. Aspirin resistance was defined as a mean aggregation of ≥70% with 10 µM ADP and ≥20% with 0.5 mg/ml Arachidonic Acid (AA). 5.2% were aspirin resistant and 94.8% were aspirin responder. During follow-up, aspirin resistance was associated with an increased risk of death, MI, or CVA compared with patients who were aspirin sensitive (24% vs. 10%, hazard ratio [HR] 3.12, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.10 to 8.90, p = 0.03). Stratified multivariate analyses identified platelet count, age, heart failure, and aspirin resistance to be independently associated with major adverse long-term outcomes (HR for aspirin resistance 4.14, 95% CI 1.42 to 12.06, p = 0.009). They concluded a three fold increase in the risk of major adverse events associated with aspirin resistance9.

Among patients treated with peripheral vascular angioplasty, Mueller et al. reported an incidence of 40% aspirin resistance with aspirin resistance being associated with an 87% increase in risk of future arterial occlusion after 18 months of clinical follow-up4.

The study by Grundmann compared the prevalence of aspirin resistance among patients with a prior stroke with patients who developed a recurrent ischemic stroke while taking aspirin. The study compared 18 post stroke patients with 25 recurrent post stroke patients on 100 mg/day aspirin. Using Platelet function analyzer (PFA-100) a rate of 34% AR was obtained among recurrent stroke patients compared with none for the asymptomatic post-stroke patients8.

Matetzky et al tried to evaluate the ill effects of clopidogrel resistance relating to cardiovascular episodes following coronary events and stenting. 60 patients undergoing primary angioplasty (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]) with stenting were prospectively studied. Patients were stratified into 4 quartiles according to the percentage reduction of ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Patients in the first quartile were resistant to the effects of clopidogrel (ADP-induced platelet aggregation at day 6, 103±8% of baseline), whereas ADP-induced aggregation was 69±3% of baseline in 2nd quartile, 58±7% of baseline in 3rd quartile and 33±12% of baseline in 4th quartile. Whereas 40% of patients in the first quartile developed a recurrent cardiovascular event during a 6-month follow-up, only 1 patient (6.7%) in the second quartile and none in the third and fourth quartiles suffered a recurrent cardiovascular event (P=0.007). They concluded that 25% of STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI with stenting are resistant to clopidogrel and therefore at increased risk for recurrent cardiovascular events21.

A prospective study included 106 NSTEACS patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stenting to assess the platelet response to both clopidogrel and aspirin. Patients were divided into quartiles according to the ADP or AA induced maximal intensity of platelet aggregation. Patients of the highest quartile (quartile 4) were defined as the 'low-responders'. Twelve recurrent cardiovascular (CV) events occurred during the 1-month follow-up. Clinical outcome was significantly associated with platelet response to clopidogrel [Quartile 4 vs. 1, 2, 3: OR (95% CI) 22.4 (4.6-109)]. Low platelet response to aspirin was significantly correlated with low response to clopidogrel (P = 0.003) but contributed less to CV events [OR (95%CI): 5.76 (1.54-35.61)] 22.

In our study aspirin, clopidogrel and dual resistance were 35%, 72.5% and 32.5% respectively among recurrent ACS patients as compared to 25.3%, 42.3% and 18.8% among patients with first ACS.

In our previous studies aspirin and clopidogrel resistance was defined as ≥70% aggregation with collagen and ADP respectively as previously published in literatures23. However this time around we accepted a ≥50% aggregation with collagen and ADP as the cut-off value as ACC/AHA 2005 guideline recommends higher maintenance clopidogrel dose in cases of less than 50% inhibition of platelet aggregation24.

Previous studies have noted that older age, female gender, and hypertension tended to be more common among aspirin resistant patients25, 26. However, a study by Berrouschot showed no significant difference in the clinical characteristics of aspirin resistant patients and aspirin responders27. A study from Manilla viewed the effects of conventional risk factors in recurrent noncardioembolic ischemic infarction. 74% of these patients were males. 87% were hypertensive, and 55% had diabetes mellitus. 37% were alcoholic beverage drinkers. More than half of the patients had hypercholesterolemia (51%) and hypertriglyceridemia (62%). Hypertension was observed in 87% patients who were aspirin responders, compared with 86% aspirin resistant patients. Diabetes mellitus was seen in 52% aspirin responders compared with 87% aspirin resistant patients. In the aspirin responder group 39% were current smokers compared with 25% in the aspirin non-responders. The study from Manilla found that the mean age of study population was 61.2 ± 10.4 years with a range of 33 to 87 years and documented a greater recurrence in elderly28.

In our study, recurrence was more common in relatively younger population (a mean age of 54.6 ±10.9 years in recurrent ACS patients vs 58.5 ±12.2 years in patients with first ACS). Conventional risk factors like diabetes, hypertension, smoking and dyslipidemia were more frequent in patients with recurrent events. Hypertension, diabetes, smoking and elevated LDL were observed in 75%, 60% 67.5% and 80% of patients respectively in recurrent ACS group.

The treatment for failed antiplatelet therapy is as yet undefined. The CURE and CREDO trials revealed the additive clinical benefit of clopidogrel to aspirin29.Beyond the use of aspirin in conjunction with clopidogrel, the options for medical therapy remain limited. Consideration can be given to increasing maintenance doses or loading doses of clopidogrel. Various studies have shown superiority of using 600 mg of clopidogrel prior to PCI when compared with 300 mg of clopidogrel as pretreatment or loading dose29,30. In an earlier study, we observed that the resistance can be overcome by increasing the maintenance dose of the respective drug 31. Other prospective add on therapy could include thienopyridine agent prasugrel (LY640315), nonthienopyridine P2Y12 inhibitors such as the intravenous agent cangrelor and the oral ADP antagonist AZD6140 (tcagrelor).29,32. Prasugrel has already been investigated in a large phase-2 study, Joint Utilization of Medications to Block Platelets Optimally—Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 26 (JUMBO-TIMI-26 )29,33 . Superiority of prasugrel has been demonstrated in TRITON TIMI 38 trial and it is now a USFDA approved drug 34. Ticagrelor is being evaluated by PLATO group. The initial reports are satisfactory and full report will be presented in ESC 2009 conference. .

Further research is necessary to determine the efficacy and safety of these alternative drugs for aspirin and clopidogrel resistance, as well as to identify factors that are associated with favorable or unfavorable responses. It is still too early to recommend routine determination of aspirin and clopidogrel responsiveness among ACS patients. However, clinicians should be aware of this entity among patients with recurrent ACS.

|

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical support rendered by Indranil Biswas and Sounik Sarkar during the experiments.

Funding Sources

The present work is sponsored by DST, Govt. of India (SR\SO\HS-84\2004).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None

References

1. Foussas SG, Zairis MN, Tsirimpis VG et al. The impact of aspirin resistance on the long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Clin Cardiol. 2009 Mar;32(3):142-7

2. Eikelboom JW, Hankey GJ. Aspirin resistance: a new independent predictor of vascular events? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41: 966– 8.

3. Michelson AD, Furman MI. Laboratory markers of platelet activation and their clinical significance. Curr Opin Hematol 1999; 6:342– 8.

4. Mueller MR, Salat A, Stangl P et al. Variable platelet response to low-dose ASA and the risk of limb deterioration in patients submitted to peripheral arterial angioplasty. Thromb Haemost 1997;78:1003–7.

5. Hurlen M, Seljeflot I, Arnesen H. The effect of different antithrombotic regimens on platelet aggregation after myocardial infarction. Scand Cardiovasc J 1998;32:233–7.

6. Grotemeyer KH, Scharafinski HW, Husstedt IW. Two-year follow-up of aspirin responder and aspirin non responder. A pilot-study including 180 post-stroke patients. Thromb Res 1993;71:397– 403.

7. Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Weitz JI, Johnston M, Yi Q, Yusuf S. Aspirin resistant thromboxane biosynthesis and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. Circulation 2002;105:1650– 5.

8. Grundmann K, Jaschonek K, Kleine B, Dichgans J, Topka H. Aspirin non-responder status in patients with recurrent cerebral ischemic attacks. J Neurol 2003;250:63– 6.

9. Gum PA, Kottke-Marchant K, Welsh PA, White J, Topol EJ. A prospective, blinded determination of the natural history of aspirin resistance among stable patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:961– 5

10. Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy—I: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ. 1994;308:81–106.

11. Mehta SR, Yusuf S; Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) Study Investigators. The Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) trial programme; rationale, design and baseline characteristics including a meta-analysis of the effects of thienopyridines in vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:2033–41.

12. O'Donoghue M, Wiviott SD. Clopidogrel response variability and future therapies: clopidogrel: does one size fit all? Circulation. 2006 Nov 28;114(22):e600-6

13. Angiolillo DJ, Shoemaker SB, Desai B et al. Randomized comparison of a high clopidogrel maintenance dose in patients with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease: results of the Optimizing Antiplatelet Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus (OPTIMUS) study. Circulation. 2007 ; 115(6):708-16.

14. Mason PJ, Jacobs AK, Freedman JE. Aspirin resistance and atherothrombotic disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(6):986-93.

15. Mckee SA, Sane DC, Deliargyris EN. Aspirin resistance in cardiovascular disease: a review of prevalence, mechanisms, and clinical significance. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88(5):711-5.

16. Michelson AD, Furman MI, Goldschmidt-Clermont P, et al. Platelet GPIIIa Pl(A) polymorphisms display different sensitivities to agonists. Circulation. 2000;101:1013–1018.

17. Beer JH, Pederiva S, Pontiggia L. Genetics of platelet receptor single-nucleotide polymorphisms: clinical implications in thrombosis. Ann Med 2000;32:10–4.

18. Von Beckerath N, von Beckerath O, Koch W, Eichinger M, Schomig A, Kastrati A. P2Y12 gene H2 haplotype is not associated with increased adenosine diphosphate- induced platelet aggregation after initiation of clopidogrel therapy with a high loading dose. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2005;16:199–204.

19. Helgason CM, Bolin KM, Hoff JA, et al. Development of aspirin resistance in persons with previous ischemic stroke. Stroke 1994; 25: 2331-6.

20. Chamorro A, Escolar G, Revilla M, et al. Ex vivo response to aspirin differs in stroke patients with single or recurrent events: a pilot study. J Neurol Sci 1999; 171: 110-14.

21. Matetzky S, Shenkman B, Guetta V, et al. Clopidogrel resistance is associated with increased risk of recurrent atherothrombotic events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004;109: 3171-3175.

22. Cuisset T, Frere C, Quilici J et al. High post-treatment platelet reactivity identified low-responders to dual antiplatelet therapy at increased risk of recurrent cardiovascular events after stenting for acute coronary syndrome. J Thromb Haemost 2006;4: 542–9.

23. Dual antiplatelet drug resistance in patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Guha S, Sardar P, Guha P et al. Indian Heart J.2009;61:68-73

24. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention—Summary Article: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). Sidney C. Smith, Jr, Ted E. Feldman, John W. Hirshfeld et al. Circulation. 2006;113:156-175

25. Alberts MJ, Bergman DL, Molner E, et al. Antiplatelet effect of aspirin in patients with cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 2004; 35; 175-8.

26. Macchi L, Petit E, Brizard A, Gil R, Neau J. Aspirin resistance in vitro and hypertension in stroke patients.J Thromb Haemost 2003; 1: 1710-3.

27. Berouschot J, Schwetlick B, von Twickel G, et al. Aspirin resistance in secondary stroke prevention. Acta Neurol Scand 2006; 113: 31-5.

28. Jose C Navarro, Annabelle Y Lao, Maricar P Yumul et al. Aspirin resistance among patients with recurrent non-cardioembolic stroke detected by rapid platelet function analyzer. Neurology Asia 2007; 12: 89 – 95.

29. Thomas H. Wang, Deepak L. Bhatt and Eric J. Topol Aspirin and clopidogrel resistance: an emerging clinical entityEur. Heart J. 27:647-654, 2006

30. Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Agostoni P et all: Meta-analysis appraising high clopidogrel loading in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.Am J Cardiol. 2007 Oct 15;100(8):1199-206

31. Dual Antiplatelet Drug Resistance in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Guha S, Sardar P, Guha P, Roy S, Mookerjee S, Chakarabarti P et al. Indian Heart J.2009;61:68-73

32. Bhatt DL, Topol EJ. Scientific and therapeutic advances in antiplatelet therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003;2:15–28.

33. Stephen D. Wiviott, Elliott M. Antman, Kenneth J. Winters, Govinda Weerakkody, Sabina A. Murphy, Bruce D. Behounek et al. Randomized Comparison of Prasugrel (CS-747, LY640315), a Novel Thienopyridine P2Y 12 Antagonist, With Clopidogrel in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Results of the Joint Utilization of Medications to Block Platelets Optimally (JUMBO)–TIMI 26 Trial. Circulation 2005;111;3366-3373;

34. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM, for the TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. NEJM 2007;357:2001-2015.

|