Prevalence of Coronary Heart Disease in the Urban Adult Males of

Eastern Nepal: A population-based analytical cross-sectional study

Abhinav Vaidya, paras Kumar Polkharel, s Nagesh, prahlad karki,

sanjay Kumar, shankhar Majhi

Department of Community Medicine, Kathmandu Medical College teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal

department of Community Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Department of Biochemistery,

B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Science, Dharan, Nepal

|

|

INTRODUCTION Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most prevalent yet one of the most preventable causes of death. Among the various types of cardiovascular diseases, coronary heart disease (CHD) is the largest cause of death, and ranks fifth in terms of disease burden.1 Whereas age-adjusted cardiovascular death rates have declined in several developed countries in past decades, rates of CVD have risen greatly in low-income and middle-income countries.2 In 1990, two-thirds of the 14 million cardiovascular fatalities worldwide occurred in the developing countries.3-5 Like other developing countries, Nepal is challenged by poverty, infectious and communicable diseases, high maternal deaths, malnutrition and lack of a competent health care system. While it has been struggling to combat the menace of communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases such as CVDs have remained largely neglected. So far Nepal far does not have a specific policy or programme regarding CVDs. Lack of proper surveillance system and appropriate policies have led to silent fostering of CVDs. To develop any kind of policy and programme, it is absolutely crucial that we first measure the burden of the problem. But very few studies have been done to deal with this rising public health problem and most of them are only hospital-based reports. Researches, if any, have been limited to certain risk factors such as hypertension or tobacco use. There is in fact not a single study reported regarding the prevalence of CHD at a community level. Hence, this research has been undertaken with the principal objective of obtaining a baseline data on prevalence of coronary heart disease and associated risk factors in urban Nepal. |

Setting and participants

A population-based analytical cross-sectional study was undertaken in the Dharan municipality in 2005-6 with one thousand males aged ≥ 35 years. Dharan is one of the three municipalities in the Sunsari District of Koshi zone in the Eastern Nepal and can be considered a prototype of most of the towns in Nepal (fig.1). It has a total population of 116 491 according to the latest census of 2001. B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) in Dharan is an important tertiary care that provides high quality health care service to the eastern region of Nepal and parts of northern India.

Fig.1: Location map of the Dharan Municipality, Nepal. |

|

E mail: dr.abhinavaidya@gmail.com

|

Sample size for the present study was calculated with the standard formula (4pq/L2) using a prevalence rate of 10% based on the studies from urban India. Sampling of the participants was done by systematic random sampling of the households with application of population proportionate to size technique. The selected households were visited between June 2005 and February 2006. In case there was more than one male aged ≥ 35 years in a household, all the males aged ≥ 35 years in that household were enlisted and by lottery method, one of them was chosen as the respondent. An adjacent household was taken if there was no male aged ≥ 35 years in the household, if the eligible respondent was currently temporarily living away and was unlikely to return in the immediate future or could not be contacted even after three visits to the household or did not consent to participate in the study.

Tools of data collection

Questions were asked in Nepali language and recorded in English language by the principal investigator. All the respondents were questioned about socio-demographic profile, dietary profile, physical activity, stress, tobacco and alcohol taking habits, etc. In addition, a section on WHO Rose angina questionnaire, which is a standardized and validated method6, 7 of measuring angina pectoris in general populations, was included to screen for angina in all except those with documented CHD. Physical examination included measurements for blood pressure, height, weight, waist and hip circumferences, and investigations included electrocardiograms in all who had positive Rose Questionnaire which was interpreted using the Minnesota Codes. The main operational definitions used in the study are presented in the table1.

Ethical approval

Ethical clearance was taken from the ethical committee of the institute (BPKIHS) and informed consent was obtained from the participants. Those with suspected coronary heart disease, any risk factor or any other disease, was appropriately advised either life-style modifications, treatment or referred to physicians or cardiologists.

Data analysis

The collected data was analysed with STATA 9.0. Chi-square test and Student’s t-test were applied to test the significance of differences among proportions and means respectively. Odds ratios with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated.

RESULTS

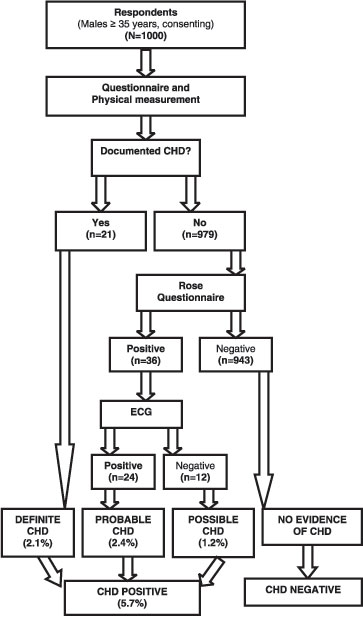

Respondents had been enquired if they had any documented history of chest pain suggestive of angina or infarction, previously diagnosed CHD including admission for a myocardial infarction or if they had undergone any coronary interventions. Twenty one of the respondents responded positively for this query, with 13 of them having history of myocardial infarction and another 8 suffering from unstable angina. Hence, the prevalence of definite CHD found in the study was 2.1% (fig.2). In the rest of the respondents who did not give a history of documented CHD (n=979), Rose questionnaire had been administered. Altogether 36 respondents responded positively to the questionnaire i.e. they had angina according to the given criteria. All of the 36 respondents with Rose angina had their resting electrocardiograms taken and interpreted, out of which ECGs of 24 respondents showed presence of electrographic changes suggestive of myocardial ischemia. These respondents with both Rose angina and ECG changes were termed ‘probable CHD’. The remainders (n=12) of the 36 respondents who had Rose angina but no suggestive ECG changes were termed ‘possible CHD’. Respondents with definite CHD, possible CHD and probable CHD were pooled together as “CHD positive” giving an overall CHD prevalence of 57/1000 (5.7%, 95%CI: 4.26 – 7.13). This combined value was used in the rest of the analysis. And the larger section of the population who had no documented history of CHD or Rose angina, were assumed to be ‘normal’ and classified as ‘CHD negative’. The association between the dependent variable (CHD) and the different independent variables was analysed and the results are presented in tables 2 & 3.

Fig.2: Flow chart illustrating the methodology of the study and the categorization of the population on the basis of CHD

|

|

Table 1: Operational Definitions

Coronary heart disease 8 |

|||

Definite CHD

|

Documented history of chest pain suggestive of angina or infarction and previously diagnosed CAD including self reported admission for a myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) |

||

Probable CHD |

Presence of both Rose angina and ECG suggestive of CHD as evidenced by the presence of electrographic changes namely Minnesota codes 1-1-1 through 1-1-7 or 1-2-1 through 1-2-7; presence of major ST-segment and major T-wave and Q-wave changes or Q-wave changes only in absence of high voltage R-wave (Minnesota codes 4-1-1 and 4-1-2 and 5-1 and 5-2). |

||

Possible CHD |

Affirmative response to Rose questionnaire after excluding any obvious cause of pain due to local factors. ECG not suggestive of CHD. |

||

Normal |

If the subject has none of the above findings. |

||

Ethnicity 9 |

|||

Major hill caste |

Included Brahmins, Chhetris, Newars |

||

Hill native |

Included Rai, Limbu, Magar, Gurung |

||

Hill occupational caste |

Included Bishwokarmas, etc. |

||

Terai caste |

Included Yadavs, Musalmans, and Tharus. |

||

Occupation |

|||

Agriculture |

landlords, or into agro-related works |

||

Ex-army |

previously serving in the British or Indian army (Lahure) |

||

Technical |

Included those who do clerical works, office-goers, businessmen and shopkeepers |

||

Labour |

Included skilled and unskilled labourers |

||

Others |

Students, politicians, priests, writers, artists, etc. |

||

Socio-economic status |

|||

Low, middle and high |

By Kutty’s scoring system10 by taking into account the educational status of the household, the land holding, the consumables owned and the type of house living in. |

||

Physical activity11 |

|||

Sedentary, light, moderate and heavy |

By asking the activities during work, leisure and in household works assigning the highest score in each category that he merits. The final score to be reckoned as the highest in any category attributed to him. |

||

Stress 11 |

Defined as feeling irritable or filled with anxiety: at home, work or if financial stress. |

||

Never; sometimes; |

0 episode in a month; < 5 episodes in a month; > 5 episodes in a month; > 5 episodes in a week |

||

Tobacco use |

|||

Non users |

If one has never smoked cigarettes, etc or chewed any form of tobacco |

||

Current users |

Currently smoking on a regular basis, one or more cigarettes, etc per day or currently using any form of tobacco. |

||

Past users |

Smoked cigarettes, etc or chewed any form of tobacco in the past but not currently. (Ex-smoker if previously smoking cigarettes.) |

||

Passive smokers |

Who do not use tobacco but are exposed to other’s smoke for a significant duration |

||

Alcohol |

|||

Never; Occasional; |

Who has never taken alcohol;1-4 times a month; >once a week; those who have quit drinking completely |

||

Hypertension |

classified according to WHO/ISH 12 as: |

||

Normotensive |

Optimal: SBP of <120 and DBP of < 80; Normal: SBP of <130 and DBP of < 85 |

||

Hypertensive |

Mild: SBP of 140-159 and DBP of 90-99; Moderate: SBP of 160-179 and DBP of 100-109; Severe: ≥180 and ≥ 110 |

||

BMI |

categorized according to the WHO criteria: 13 |

||

Underweight;normal; |

if BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 ;18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2; 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2; ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 |

||

|

Table 2: Comparison of the CHD positive and CHD negative population in terms of their socio-demographic characteristics

Characteristics |

CHD positive |

CHD negative |

OR |

Adjusted OR |

Age (years) |

|

|

|

|

35-49 |

9 (1.9) |

466 (98.1) |

Ref |

Ref |

50-64 |

20 (6.2) |

305 (93.8) |

3.39 ( 1.52-7.55) |

1.97(0.79- 4.88) |

≥ 65 |

28 (14.0) |

172 (86.0) |

8.43 (3.90-18.22) |

2.73(0.98 -7.60) |

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

Terai caste |

0(0.0) |

23(100.0) |

|

|

Major hill caste |

33(6.8) |

452(93.2) |

Ref |

Ref |

Hill native caste |

19(4.6) |

397(95.4) |

0.65 (0.36-1.17) |

0.32 (0.07 - 1.37) |

Hill occupational caste |

5(6.6) |

71(93.4) |

0.96(0.36- 2.55) |

0.90 (0.26 - 3.11) |

Religion |

|

|

|

|

Hinduism |

35 (6.5) |

503 (93.5) |

Ref |

Ref |

Buddhism / Kirat |

22 (5.0) |

418 (95.0) |

0.75(0.44- 1.31) |

1.32 ( 0.33-5.20 ) |

Others |

0 (0.0) |

22 (100.0) |

- |

|

Marital Status |

|

|

|

|

Single |

3 (7.1) |

39 (92.9) |

Ref |

Ref |

Married |

54 (5.6) |

904 (94.4) |

0.89(0.26- 3.03) |

1.52 (0.38 -6.14) |

Level of education |

|

|

|

|

Illiterate |

21 (8.8) |

219 (91.3) |

Ref |

Ref |

School education |

30 (5.1) |

562 (94.9) |

0.55(0.31- 0.99) |

0.53 (0.25 - 1.14) |

Higher education |

6 (3.6) |

162 (96.4) |

0.38(0.15- 0.97) |

0.33 (0.08 - 1.34) |

Current job status |

|

|

|

|

Employed |

21 (3.1) |

650 (96.9) |

Ref |

Ref |

Retired |

36 (10.9) |

293 (89.1) |

3.79(2.17- 6.61) |

2.37 (0.10- 5.62) |

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

Labour |

6 (2.6) |

227 (97.4) |

Ref |

Ref |

Agriculture |

18 (11.1) |

144 (88.9) |

4.73 (1.83- 12.19) |

1.26(0.40 -4.00) |

Ex-army |

11 (8.3) |

121 (91.7) |

3.43 (1.24- 9.52) |

1.08 (0.26 -4.40) |

Technical |

21 (5.1) |

393 (94.9) |

2.02 (0 .80- 5.08) |

0.90 ( 0.27-3.02) |

Others |

1 (1.7) |

58 (98.3) |

0.65(0.07- 5.52) |

0.25 (0.02- 2.70) |

Socio-economic status |

|

|

|

|

Low |

20 (4.5) |

428 (95.5) |

Ref |

Ref |

Middle |

34 (7.2) |

436 (92.8) |

1.66(0.94- 2.94) |

1.71 (0.77-3.78) |

High |

3 (3.7) |

79 (96.3) |

0.81(0.23- 2.79) |

1.08 (0.24-4.91) |

Ref: Reference value

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of CHD

The WHO (Rose) chest pain questionnaire

Unlike the CHD cases seen in the hospitals that generally present with the typical coronary symptoms, detection of CHD cases in a free-living community is a difficult task. The conventional methods include the tools such as Rose angina questionnaire, that rely on the history of chest pain, and, electrocardiography, both of which have got their own limitations. More specific techniques such as coronary angiography are invasive and hence impractical.

|

Table 3: Comparison of the CHD positive and CHD negative population in terms of their life-style and anthropometric characteristics

Characteristics |

CHD positive |

CHD negative |

OR |

Adjusted OR |

Dietary habit |

|

|

|

|

Vegetarian |

10 (9.4) |

96 (90.6) |

Ref |

Ref |

Non-vegetarian |

47 (5.3) |

847 (94.7) |

0.52(0.24- 1.10) |

0.61(0.24-1.51) |

Physical activity |

|

|

|

|

Sedentary |

8 (10.3) |

70 (89.7) |

Ref |

Ref |

Light |

31 (8.5) |

332 (91.5) |

0.82(0.36-1.85) |

1.35 (0.51-3.56) |

Moderate |

13 (3.7) |

334 (96.3) |

0.34(0.13-0.85) |

0.69 (0.24-2.05) |

Heavy |

5 (2.4) |

207 (97.6) |

0.21(0.06- 0.66) |

0.72 (0.16-3.28) |

Family history for CHD |

|

|

|

|

Absent |

52 (5.4) |

917 (94.6) |

Ref |

Ref |

Present |

5 (16.1) |

26 (83.9) |

3.39 (1.25-9.19) |

5.85 (1.53 -22.31) |

Stress history |

|

|

|

|

Never/rare |

5 (2.6) |

185 (97.4) |

Ref |

Ref |

Sometimes |

28 (4.8) |

561 (95.2) |

1.84 (0.70-4.85) |

1.63 (0.59-4.53) |

Often |

18 (10.6) |

152 (89.4) |

4.38(1.59-12.07) |

4.26 (1.39-13.10) |

Always |

6 (11.8) |

45 (88.2) |

4.93 (1.44-16.89) |

3.46 (0.87-13.80) |

Alcohol intake |

|

|

|

|

Never |

17 (5.8) |

277 (94.2) |

Ref |

Ref |

Occasional |

3 (2.7) |

110 (97.3) |

0.44 (0.13-1.54) |

0.77(0.19-3.06) |

Frequent |

16 (3.9) |

391 (96.1) |

0.67 (0.33-1.34) |

1.17 (0.49-2.80) |

Previously drinking |

21 (11.3) |

165 (88.7) |

2.07(1.06-4.04) |

1.89(0.77-4.64) |

Tobacco intake |

|

|

|

|

Never |

16 (3.1) |

494 (96.9) |

Ref |

Ref |

Current |

19 (7.3) |

241(92.7) |

2.43 (1.23-4.82) |

1.75 (0.79-3.89) |

Past |

22 (9.6) |

208 (90.4) |

3.27 (1.68- 6.34) |

2.96 (1.30-6.76) |

Blood pressure |

|

|

|

|

Normotensive |

9 (4.6) |

187 (95.4) |

Ref |

Ref |

Pre-Hypertensive |

28 (4.8) |

549 (95.2) |

1.06(0.49-2.29) |

0.83 (0.34-1.99) |

Hypertensive, stage 1 |

9 (6.5) |

129 (93.5) |

1.45(0.56-3.75) |

1.15 (0.39-3.43) |

Hypertensive, stage 2 |

11 (12.4) |

78 (87.6) |

2.93( 1.17-7.35) |

2.00 (0.68-5.87) |

Body Mass Index |

|

|

|

|

Underweight |

1 (4.0) |

24 (96.0) |

Ref |

Ref |

Normal |

32 (5.6) |

542 (94.4) |

1.41( 0.18-10.8) |

0.98(0.10-8.99) |

Overweight |

21 (6.38) |

308 (93.6) |

1.64 ( 0.21-12.69) |

1.15 (0.12-11.00) |

Obese |

3 (4.17) |

69 (95.83) |

1.04 ( 0.10-10.52) |

0.75 (0.06-9.75) |

Waist Hip Ratio |

|

|

|

|

Normal |

25 (5.1) |

463 (94.9) |

Ref |

Ref |

High |

32 (6.3) |

480 (93.8) |

1.23(0.72-2.11) |

1.09 (0.57-2.07) |

Ref: Reference value

Table 4: Comparison of the findings of this study with selected studies from India*

First author |

Year |

Place |

Urban |

Age |

Sample |

Overall prevalence |

Diagnosis by history (men) |

Diagnosis by ECG (men) |

Definite |

Mathur 16 |

1960 |

Agra |

Urban |

NA |

1046 |

1.05 |

|

|

|

Padmavati 17 |

1962 |

Delhi |

Urban |

NA |

1642 |

1.04 |

|

|

|

Chaddha 14 |

1990 |

Delhi |

Urban |

25-64 |

13723 |

9.67 |

3.95 |

5.63 |

|

Kutty 10 |

1993 |

Kerala |

Rural |

>25 |

1130 |

7.43 |

|

|

1.4 |

Gupta 15 |

1995 |

Jaipur |

Urban |

>20 |

2212 |

6 |

|

3.5 |

|

This study |

2004-5 |

Dharan, |

Urban |

≥35 |

1000 |

5.7 |

3.6 |

2.4 |

2.1 |

* Adapted from Gupta et al. South Asian J preventive cardiology 1997; 1: 27-32. NA: information not available

|

The Rose questionnaire is a screening tool originally designed for use in men and has consistently been shown to be predictive of major ischaemic heart disease events particularly in the middle aged men. For example, in a population-based prospective study18 on 7735 randomly selected men, who were administered questionnaire at baseline and followed-up for first major ischaemic heart disease event, the relative risks (95% CI) of a major ischaemic heart disease event were 2.03 (1.61, 2.57) for angina compared to no chest pain. Similarly, the association between Rose questionnaire angina pectoris and coronary calcification investigated in the Rotterdam Coronary Calcification Study19 found the presence angina pectoris was strongly associated with a 12.9-fold (95% CI: 3.8-43.7) increased risk of a calcium score >1000.

Reports have shown the questionnaire to be more specific in males than in females. For example, Garber CE et al20 compared "Rose Questionnaire Angina" to exercise thallium scintigraphy and found that though the sensitivity of the Questionnaire was similar in females (41%) and males (44%), the specificity was significantly lower in females than in males (56% vs 77%). However, the performance of the Rose angina questionnaire has been sufficiently inconsistent to warrant a more objective diagnostic method to verify it, particularly to achieve greater cross-cultural validity.

Coronary risk factors

Premature CHD, defined as CHD before the age of 55 years in men, was found to be prevalent in 2.3% of the study population who were aged 55 years or less. The mean age of CHD positive respondents in our study was 64.65±12.65 years, marginally higher compared to 62.5±9.8 years in a Moradabad study21. Likewise, in the Jaipur Heart watch-2 study15, CAD was more prevalent as the age advanced (10.25% in 40-49 years, 19% in 50-59 years and 23.45% in >60 years). The corresponding figures for our study were 9%, 11% and 37%. The prevalence of CHD in the youngest age group 20-29 years of the Jaipur study was even higher (3.3%) than that in our youngest age-group which was 35-49 years. So it is likely that the CHD is not very prevalent in the younger age group in our context in contrast to the scenario in India where more and more young adults are being affected with CHD.

Employment and CHD have been associated in many studies. In our study, the retired had CHD more than the employed (10.9% vs. 3.1%) which was highly significant statistically (p< 0.001). But the association did not remain significant (p=0.129) after adjusting for age confirming the effect of age as a confounder in the association between employment and CHD.

Physical activity was significantly associated with CHD in our study (p=0.002) with increasing prevalence of CHD seen in those who were not physically active. After age-adjustment, however, the association was no longer significant as the elder people were significantly less physically active than the youngsters. Similarly, CHD was more common in those who reported to have more stress in their lives (p=0.002) than those who did not. The odd of having CHD was 4 times more in those who reported to have rare episodes of stress in comparison to those who were always stressed. Other studies have also found up to 3-fold increased risk of CHD in men.22-24 However, reports25 also have shown that people who perceive and report their life to be most stressful also tend to over-report symptoms of CHD thus leading to a spurious exposure-outcome association. In our study also, 7.8% & 6.5% of those who were often (>5 episodes a month) or always (>5 times a week) stressed reported positively to Rose angina questionnaire in contrary to 2.0% and 1.1% in those who reported stress to be occurring sometimes (<5times a week) or rarely.

Family history was strongly and significantly associated with CHD in our study. After adjusting for age and other risk factors, the probability of having CHD was more than 5 times higher in those who had a positive family history of premature CHD in comparison to those who did not have. Our findings are similar to advanced studies which have found a relative odds of 1.93 (1.25-3) in a prospective study26 & OR of 2.18 in a case-control study.27

|

This is the first population-based prevalence study of coronary heart disease in Nepal and the burden of CHD in this population seems to follow the trend of India. Among the international studies on coronary heart disease in which Nepal had participted, Interheart11 is a recent, large, international, standardized, case-control study and the most important risk factors according to the study were smoking, hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, psychological factors, consumption of fruits, vegetables, and alcohol, and physical inactivity. On the other hand, the important factors associated with CHD in our study included tobacco use, age, history of hypertension and family history. It is very likely that diabetes and dyslipidemia are also vital risk factors in this study population but as they had not been thoroughly explored, not much can be commented upon regarding their significance in the study population. Nevertheless, it is quite likely that the factors found in the Interheart study are important to this study population too. The bottomline is that Public health policies and programmes to address CVDs including CHD and the associated risk factors are urgently required in Nepal.

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

REFERENCE

-

Murray CJL, Lopez A, Eds. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA, Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank, 1996.

-

Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases, part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation 2001; 104: 2746-53.

-

Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global comparative assessments in the health sector. Geneva. Switzerland. World health Organization.1994.

-

Dodu SRA. Emergence of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Cardiology 1988; 75: 56-64.

-

Chuckalingam A. Balaguer- Vintro I. Impending global pandemic of cardiovascular disease. World Heart Federation. Prous Science. Barcelona, Spain. 1999.

-

Rose GA, Blackburn H, Gillum RF, Prineas RJ. Cardiovascular survey Methods (2nd edition) WHO Geneva 1982.

-

Rose GA. The diagnosis of ischaemic heart pain and intermittent claudication in field surveys. Bull Wld Hlth Org 1962; 27:645–58.

-

Rajdurai A, Arploas J, Pasamanickam K, Shatar A, Meilin O. Coronary artery disease in Asian. Aust NZ J. Med 1992; 22: 345-348.

-

Sunsari Health Examination Survey. B. P. Koirala Institute of Health sciences and His Majesty’s Government, Ministry of Health 1996.

- Kutty VR, Balakrishnan KG, Jayasree AK, Thomas J. Prevalence of coronary heart disease in the rural population of Thiruvananthapuram district, Kerala, India. International Journal of Cardiology 1993; 39: 59-70.

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case–control study. Lancet 2004; 364(9438): 937–952.

- Chalmers J, MacMahon S, Mancia G, Whitworth J, Beilin L, Hansson L et al. Classification of hypertension according to WHO/ISH. J Hypertens 1999; 17:151–185.

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity. Geneva, 3-5 June, 1997. WHO/NUT/NCD/98.1. Technical Report Series Number 894. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000.

- Chadha SL, Radhakrishnan S, Ramachandran K, Kaul U, Gopinath N. Epidemiological study of coronary heart disease in urban population of Delhi. Indian J Med Res 1990; 92: 424-430.

- Gupta R, Gupta VP, Sarna M, Bhatnagar S, Thamvi J, Sharma V, Singh AK, Gupta JB, Kaul V. Prevalence of coronary heart disease and risk factors in an urban Indian population: Jaipur Heart Watch-2. Indian Heart J 2002; 54: 59-66.

- Mathur KS. Environmental factors in coronary heart disease. An epidemiologic study at Agra. Circulation 1960; 21: 684.

- Padmawati S. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in India. II. Ischemic heart disease. Circulation 1962; 25: 711.

- Lampe FC, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Ebrahim S, Walker M, Shaper AG. Chest pain on questionnaire and prediction of major ischaemic heart disease events in men. Eur Heart J 1998; 19:63–73.

- Oei HH, Vliegenthart R, Deckers JW, Hofman A, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC. The association of Rose questionnaire angina pectoris and coronary calcification in a general population: The Rotterdam Coronary Calcification Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2004; 4(6):431-436.

- Garber CE, Carleton RA, Heller GV. Comparison of "Rose Questionnaire Angina" to exercise thallium scintigraphy: different findings in males and females. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992; 45(7):715-20.

- Singh RB, Niaz MA. Coronary risk factors in Indians. Lancet 1995:346: 778-9.

- Hippisley Cox J, Fielding K, Pringle M. Depression as a risk factor for ischemic heart disease in men: population based case-control study. BMJ 1998; 316: 1714-18.

- Everson SA, Goldberg DE, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Pukkala E,. Tuomilento J, et al. Hopelessness and risk of mortality and incidence of myocardial infarction and cancer. Psychosom Med 1996; 58: 113-21.

- F Rasul, S A Stansfeld, C L Hart, G Davey Smith. Psychological distress, physical illness, and risk of coronary heart disease. J Epidemial Community Health 2005; 59: 140-145.

- J Macleod, G Davey Smith, P Heslop, C Metcalfe, D Carroll, C Hart. Limitations of adjustment for reporting tendency in observational studies of stress and self- reported coronary heart disease. J Epidemial Community Health 2002; 56: 76-77.

- Colditz GA, Rimm EB, Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Willett WC. A prospective study of parental history of myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease in men. Am J Cardiol. 1991; 67:933-938.

- Ciruzzi M, Schargrodsky M, and Rozlosnik J for the Argentine Fricas Investigators. Frequency of family history of acute myocardial infarction in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arn ] Cardiol. 1997; 80:122-127.

- Gupta R, Prakash H, and Gupta VP. Prevalence and determinants of coronary heart disease in a rural population of India. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50: 203.

- Pais P, Fay MP, Yusuf S. Increased risk of acute myocardial infarction associated with beedi and cigarette smoking in Indians: final report on tobacco risks from a case-control study. Indian Heart J 2001; 53: 731-735.

- Jiang HE. Passive smoking and the risk of coronary heart disease- a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. The New England Journal of Medicine 1999; 920: 3.

|