Polypill in Cardiovascular Disease:Has it’s time come?

Velmurugan Kuppuswamy, Wai Kah Choo, Sandeep Gupta

INTRODUCTION Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) is the leading cause of death globally; contributing to around 17.5 million deaths worldwide in 2005 (1); 80% percent of these deaths occur in lower and middle-income countries. Once a disease of the affluent, CVD has now emerged as the number one killer in India. (2) A 6-fold increase in the incidence of CVD is seen in urban India in the last 5 decades, and a doubling in prevalence of CVD is seen in rural India in the last 3 decades. (3) The prevalence of CVD in individuals over 35 years currently stands at 10%.(4) The World Health Organization (WHO) had warned that CVD-related mortality in India will increase to epidemic proportion by 2020. (5) For an effective and successful reduction of the impact of CVD on global health and economy will require key preventative measures and strategies. Currently there is an emphasis on reducing: “single risk factors in a minority of patients to achieve national targets”. (6) As a result, most secondary prevention programmes have only produced modest results – inadequate prescription, poor adherence, and unaffordable costs are amongst the explanations. A more inclusive preventive strategy aimed at reducing all risk factors to a minimum for all moderate- and high-risk individuals seems pertinent. This paper aims to review the current evidence for a fixed-dose multi-drug combination or a “Polypill“ in the prevention of CVD and in improving adherence and affordability in the developing countries. The focus will be on both primary and secondary prevention of CVD.

What is the “Polypill”? Such a “single daily pill” called ”the Polypill” would comprise a statin, three anti-hypertensives, folic acid and aspirin. The Polypill was estimated to reduce CHD events by 88% (95% CI of 84-91%) and stroke by 80% (95% CI of 71-87%) as illustrated in Table 1. One third taking the pill above the age of 55 years were expected to gain 11 years of CVD event-free life. The combined adverse effects of all drugs would be seen in less than 15% of the study population. |

Table 1 Effects of the Polypill on CHD and stroke risk after 2 years of treatment at age 55-64 years

|

|

% Reduction in risk |

||||

Risk factor |

Agent |

Reduction in risk factor |

IHD event |

Stroke |

||

LDL-Cholesterol |

Statin |

1.8 mmol/l (70 mg/dl) |

61 (51 to 71) |

17 (9 to 25) |

||

Blood pressure |

3 classes of drugs at ½ dose |

11 mm Hg diastolic |

46 (39 to 53) |

63 (55 to 70) |

||

Platelet function |

Aspirin 75 mg/d |

3 mmol/l |

32 (23 to 40) |

16 (7 to 25) |

||

Serum Homocysteine |

Folic acid |

Not quantified |

16 (11 to 20) |

24 (15 to 33) |

||

Combined effect |

All |

|

88 (84 to 91) |

80 (71 to 87) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

LDL=low density lipoprotein. *95% confidence intervals include imprecision of the estimates of both the agent reducing the risk factor and the risk factor reduction decreasing risk. †Atorvastatin 10 mg/day, or simvastatin or lovastatin 40 mg/day taken in the evening or 80 mg/day taken in the morning

Adapted and modified from Law et al BMJ 2003

What is the rationale for the “Polypill”?

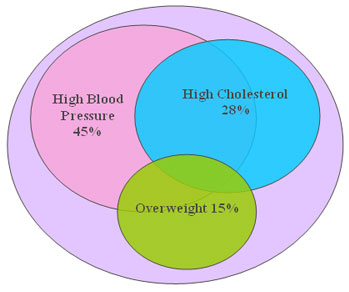

The INTERHEART study concluded that 9 conventional CVD risk factors accounted for 90% of cardiovascular risks. (8) Three most poweerful risk factors – hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and obesity – account for more than 80% of Global CVD burden (figure 1). The Health Professionals Follow-up study concluded that 62% of all coronary events could be avoided had all men adhered to a healthy lifestyle.(9)

While lifestyle and dietary modifications are vital, they are more often not sufficient in themselves. Although, pharmacotherapy for primary and secondary prevention of CVD is highly effective as proven by various trials (Table 2), current preventive strategies for CVD in real life have only produced modest results. Other issues with current multiple-drug regimens such as inadequate prescription, poor adherence to medications and the costs of multiple drugs could make the Polypill a more plausible option.

Email: sgupta111@aol.com, Fax: 44-8502-4451, Tel: 44-7961-379-928

|

|

Figure 1: Global CVD Burden Due to High Blood Pressure, Cholesterol, and Overweight |

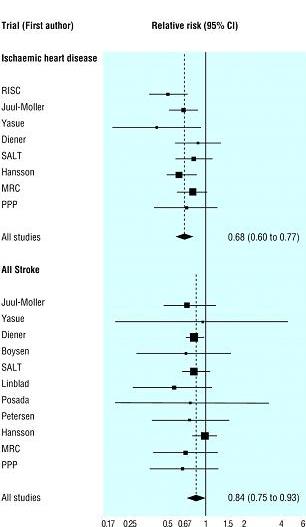

Table 2: Relative risks of clinical events for primary and secondary prevention with selected drugs

|

Death |

Ischaemic Heart Disease (95% CI) |

Stroke |

Primary prevention |

|||

Aspirin |

-- |

0.68 (0.60-0.77) |

0.84 (0.75-0.93) |

ACEi and Calcium-channel blocker |

-- |

0.66 (0.60-0.71) |

0.51 (0.45-0.58) |

Statin |

-- |

0.64 (0.55-0.74) |

0.94 (0.78-1.14) |

Secondary prevention |

|||

Aspirin |

0.85 (0.81-0.89) |

0.66 (0.60-0.72) |

0.78 (0.72-0.84) |

b-blocker |

0.77 (0.69-0.85) |

0.73 (0.75-0.87) |

0.71 (0.68-0.74) |

ACEi |

0.84 (0.75-0.95) |

0.80 (0.70-0.90) |

0.68 (0.56-0.84) |

Statin |

0.78 (0.69-0.87) |

0.71 (0.62-0.82) |

0.81 (0.66-1.00) |

Gaziano A T et al , Lancet 2006

Inadequate prescription: “The treatment gap”

Under-treatment with mediacal therapy of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is well documented. The EUROASPIRE II survey observed 20%, 33% and 53.9% prevalence in smoking, obesity and uncontrolled blood pressure in patients with CHD. (10) Only 43% and 57.5% were on ACE inhibitors and statins respectively. Similar trends were observed in the EUROASPIRE III study, (11) and Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) registries. (12)

The World Health Organization study on Prevention of Recurrences of Myocardial Infarction and Stroke (WHOPREMISE) found a concerning record on secondary prevention mostly in low and middle-income countries. (13) This study examined the proportion of patients with CVD receiving recommended pharmacological agents in 10 low and middle-income countries. Amongst those with CHD, 81.2% received aspirin, but only 48.1%, 39.8% and 29.8% received beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors and statins respectively. Amongst those with cerebrovascular disease, 70.6% received aspirin, but only 22.8%, 27.8% and 14.1% received betablockers, ACE inhibitors and statins respectively.

Government-driven initiatives to improve prescribing practices are common to a few European countries. For example, in the UK, General Practitioners receive reumeration for preventive efforts and this has been highly successful in patients being screened and achieving targets for blood sugar, cholesterol, blood pressure, etc. Such initiatives do merit consideration in Developing countries.

Poor adherence with secondary prevention: “Five pills versus a single pill”

The use of combination pharmacological therapies is independently and strongly associated with reduction in mortality. In a study involving 2,119 post-myocardial infarction patients, 97% who received aspirin, beta blockers and statins survived the first year compared with only 88% in those who received none, one or two of these medications. (14) A separate multivariable survival analysis showed that discontinuation of secondary prevention therapy was independently associated with four times increased 1-year mortality. (15)

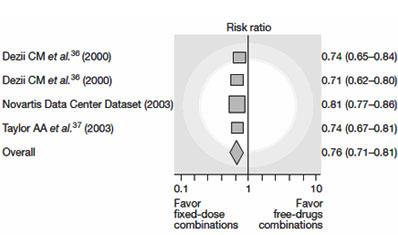

Non-compliance is responsible for almost 10% of all hospital admissions and compliance to treatment in chronic conditions may be as low as 50%.(16) Old age, psychiatric disorders and complexity of treatment are main predictors of poor compliance. (17) Compliance strongly correlates with the number of pills taken a day. Taking only one tablet a day could improve adherence. The effectiveness of the Polypill has been tested and proven in the treatments of AIDS, tuberculosis and hypertension. A meta-analysis of four hypertension trials showed that fixed-dose combination therapy could decrease the risk of non-compliance by a quarter compared to conventional treatments (Figure 2). (18)

|

Figure 2: Effect of Fixed-dose combination on treatment adherence in patients with hypertension |

|

Multiple medications for CVD: Is it affordable in developing countries?

Secondary prevention is cost-effective to the economy. Table 3 shows the incremental cost-effectiveness of a hypothetical Polypill for CVD prevention by region. The cost effectiveness of secondary prevention does not necessarily ensure affordability in middle and lower income countries. Affordability in a developing economy is defined differently as work-days required by lowest-waged public servicemen to purchase a month-long supply of generic secondary prevention drugs. Furthermore out-of-pocket expenditure on health is also much higher in developing than in developed nations.

A model on cost-effectiveness of a hypothetical polypill in preventing CVD in India showed favourable outcomes (table 4). These estimates suggest that despite a higher cost per DALY in treating lower risk patients, the overall incremental cost-effectiveness ratio remains positive. Multiple drug regimen for secondary prevention as currently practiced may not be affordable to people in lower and mid income countries. (19) In India, fixed-dose combinations of patented drugs have been used with proven affordability in the treatment of non-cardiovascular diseases.

Figure 3: Estimates of Cost-effectiveness of a Polypill for CVD, by Region

|

Incremental Cost-effectiveness |

|||

Region |

> 35 % Risk |

> 25 % Risk |

> 15 % Risk |

>5 % Risk |

East Asia and the Pacific |

$830 |

$1,440 |

$2,320 |

$3,820 |

Europe and Central Asia |

$940 |

$1,450 |

$1,960 |

$3,620 |

Latin American and the Caribbean |

$920 |

$1,470 |

$2,420 |

$3,740 |

Middle East and North Africa |

$720 |

$1,290 |

$2,190 |

$4,030 |

South Asia |

$670 |

$1,250 |

$1,932 |

$3,020 |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

$610 |

$1,170 |

$1,920 |

$2,960 |

Notes: The risk refers to a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease.

Source: Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, second edition, 2006

Figure 4: Estimates of Cost-effectiveness of a Polypill for Cardiovascular Disease in India

Costs and Effects |

No Polypill |

>35 % Risk |

> 25 % Risk |

> 15 % Risk |

>5 % Risk |

Total cost (millions) |

$23.5 |

$34.5 |

$51.4 |

$92.2 |

$205.2 |

MI averted |

n.a. |

10,200 |

14,400 |

21,300 |

31,800 |

CHD deaths averted |

n.a. |

10,500 |

13,500 |

19,600 |

25,900 |

Stroke deaths averted |

n.a. |

5,900 |

7,500 |

10,500 |

14,200 |

DALYs averted |

n.a. |

41,000 |

57,000 |

86,000 |

134,000 |

Incremental cost-effectiveness (cost per DALY averted) |

n.a. |

$300 |

$990 |

$1,500 |

$2,430 |

Notes: For a population of one million adults for treatment over 10 years. Each strategy is compared with no polypill. (n.a. = not applicable)

Source: Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, second edition, 2006

Fixed-dose combination therapy: selection of drugs

Since Wald and Law’s Polypill was proposed in 2003, various combinations have also been suggested as highlighted in Table 6. A Spanish group proposed a combination of 100mg uncoated aspirin, 40mg simvastatin and ramipril at three different doses (2.5, 5 and 10mg) to facilitate dose titration. An Indian group evaluated a combination of 100mg of aspirin and simvastatin with three antihypertensives at low doses - atenolol, ramipril and thiazide.

Statins

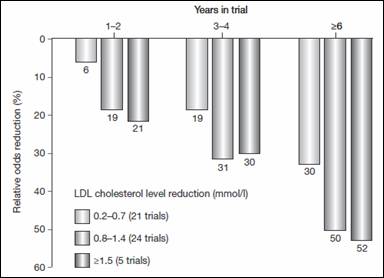

Evidence supporting clinical efficacy for statins is strong. The Law et al. meta-analysis (2003) suggested that a 1.5 mmol/l reduction in LDL cholesterol will reduce cardiovascular events by 20-50% (figure 3). (20) Such reduction can be achieved by most statins.

The Prospective Studies Collaboration group examined 61 prospective studies in a meta-analysis.(21) It demonstrated that total cholesterol level has a positive correlation with mortality related to CHD. The study also concluded that statins can reduce both coronary and cerebrovascular events. The recently published JUPITER study demonstrated the benefits of statins in people without previous CVD.(22) Therefore, statins should be a cornerstone component in the fixed-dose combination pill.

Figure 3: Reduction in the risk of ischemic heart disease events according to LDL cholesterol level and years in treatment

Data obtained from Law et al. The columns represent reduction in the risk of ischemic heart disease events according to duration of treatment and the mean reduction in LDL cholesterol achieved in each trial.

Anti-hypertensives therapies

Observational studies have suggested a correlation between blood pressure and risk of CVD. Anti-hypertensives will not only reduce CVD risks in those with hypertension, but also in those without. Current American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines recommend ACE inhibitors for patients following myocardial infarction, even in the absence of left ventricular dysfunction.

|

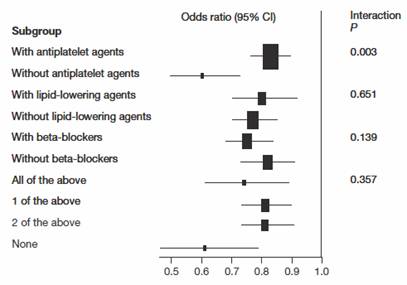

Two meta-analysis examined approximately 30,000 patients in the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE), Prevention of Events with Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition (PEACE), and the European Trial on Reduction of Cardiac Events with Perindopril in Stable Coronary Artery Disease (EUROPA). ACE inhibitors were found to reduce mortality by 14% (odds ratio 0.86, 95% CI 0.79–0.94). (23;24) ACE inhibitors remain effective even when administered together with antiplatelet, lipid-lowering agents and beta-blockers.(24) This is important in the development of combination therapies (Figure 4).

Law et al. in a meta-analysis of 147 randomised control trial suggested that the proportional reduction in cardiovascular disease events was the same or similar regardless of pre-treatment blood pressure and presence or absence of CVD. Therefore, it was suggested that lowering blood pressure in everyone over a certain age would be beneficial, rather than measuring, monitoring and only treating those with hypertension. (25)

Figure 4: Effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors on mortality in different subgroups of high-risk patients.

Permission to be obtained from Elsevier Ltd © Dagenais GR et al. (2006) Lancet

Antiplatelet agents

Aspirin is a key component in cardiovascular prevention; therefore should be included in any fixed dose combination pill. A meta-analysis by the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration group showed the positive benefits of antiplatelet treatment in patients’ post-myocardial infarction (Figure 5).

Antiplatelets could reduce the incidence of any new events significantly. For every 1,000 antiplatelet recipients, 18 nonfatal reinfarctions, 5 nonfatal strokes and 14 vascular deaths were prevented. (26) This study also concluded no significant differences in efficacy between high and low doses of aspirin; the vascular event rates were 14.1% and 14.5% for 500–1500 mg aspirin and 75–325 mg aspirin, respectively. At present, 75–162 mg of aspirin is recommended for ACS.

Figure 5: Aspirin in secondary prevention

Data and Figure obtained and modified from Law et al.

Beta blockers

Long-term treatment with beta blockers after ACS reduces mortality by about 20% and sudden death by 34%. (27) Trials on atenolol, metoprolol, propranolol and timolol concluded that beta-blockers are prognostic up to approximately 2 years after ACS. No differences in efficacy exist between them. Nevertheless, those with appreciable intrinsic sympathomimetic activity may provide greater benefit.

Despite numerous side effects, discontinuation of beta-blockers was not necessary in most cases. Adverse effects can often be minimized by changing the type of beta blocker or adjusting the dose. A Polypill with different beta blocker doses is viable.

|

Wald and Law hypothesized the benefit of Polypill in primary prevention.(7) In contrary to the current strategy of risk stratification, they suggested that everyone over 55 years could benefit from the Polypill. Stratifying patients on gender and lifestyle would add little value to outcome, but increases cost and complexity. Age was said to be a good screening tool since 96% of deaths from CHD or stroke occur in people aged 55 and above.

Several trials on the Polypill in primary prevention are ongoing worldwide. In India, two main companies involved in the development of fixed-dose combination pills for prevention of CVD are Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd (Hyderabad) and Cadila Pharmaceuticals (Ahmedabad).

The ‘Red Heart Pill’ by Dr Reddy’s laboratory, comprising aspirin (75mg), simvastatin (10mg), lisinopril (10mg) and hydrochlorothiazide (12.5mg), is being studied in 6 countries. It is targeted at patients with an estimated 10-year total WHO CVD risk score of more than 20% with an aim of primary prevention. The typical patient who would be prescribed this Polypill would be a 55-year-old man, or slightly older woman, who smokes and is overweight. The pill is expected not to exceed the cost of 1,000 Indian Rupees per person per year.

The Indian Polycap Study (TIPS), courtesy of Cadila Pharmaceuticals, used combination pills aspirin, simvastatin and three antihypertensives in low doses (atenolol, ramipril and thiazide). (28) In a 12-week period 400 participants were this Polypill. Eight other groups of 200 participants each were given either individual components or groups of them.

A 6-7mmHg reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure was seen in the Polycap group. These reductions could reduce CVD risks by 62% and stroke by 48%. The combination pill was almost as effective as individual pills with no increased side effects. The total cost for the five generic drugs is USD 17 per year (INR 840). A Polypill is expected to cost far less while providing patients with a advantage of taking fewer pills.

Other on-going primary prevention trials are as shown in Table 6.

Table 6: Ongoing Polypill Trials for primary and secondary prevention

Study (n=patient) |

Primary/secondary prevention |

No of drugs |

The Indian Polypill Study (TIPS) |

Primary |

5* |

Red Heart Pill Pilot Study**(n= 700) |

Primary |

4 |

IMPACT** (n=600) |

Primary |

4 |

INDIAN Study** (n=250) |

Secondary |

4 |

SPANISH study |

Secondary |

3¥ |

** Auckland University Newzeland and Dr Reddy’d Laboratories Ltd

* Aspirin, Statin, ACE-Inhibitor, Beta-blocker and Thiazide

¥ Aspirin, Statin and ACE-Inhibitor

Secondary prevention trials

Several trials on secondary prevention are also ongoing worldwide. The Indian Polypill Pilot study is being conducted by Dr Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd in collaboration with Auckland University of New Zealand. The National Center for Cardiovascular Research (CNIC) in Spain aims to launch a 3-drug polypill, comprising aspirin, statin and an ACEI, by 2010, for less than 10US dollar a month.

Conclusion, challenges and future direction

The concept of a Polypill in CVD is simple and attractive. All the component drugs are available generically and therefore it would be inexpensive to treat most of the CHD risk factors. Combining them in one pill could reduce CHD and stroke by 80%. This approach unsurprisingly has enormous appeal and considerable implications for global health as CVD is the leading cause of death worldwide. While Polypills have been used to treat various diseases, one targeting CHD and stroke still remain hypothetical today.

There are still ongoing concerns/issues on the Polypill. Although the Polypil reduces the number of pills to be consumed, individual regimens cannot be tailored. Polypill also risks giving too few medications, or too many, in which case exposing patients to side effects otherwise could be averted. Some of these concerns were addressed by the Indian Polycap Study (TIPS). The study showed that individual drug components in a Polypill could fulfil their roles. The combined pill was almost as effective as the individual pills with no increase in side effects. Most of all, it was was tolerable.

The major appeal of the Polypill is its simplicity and low cost hence promising compliance. Such appeal could have broad applicability in areas of the world with limited access to medical treatment. Fewer consultations will be needed to initiate this pill ensuring lifelong CV prevention. The Polypill is also applicable in modern healthcare if large proportions of high-risk patients remain untreated. Whether the Polypill can reduce CHD and stroke mortality by 80% and or add 11 event free years to everyone above 55 years as predicted remains to be seen but the initial results raises hope. In conjunction with lifestyle medications, the Polypill could one day substantially reduce the burden of CVD worldwide.

Some questions do remained unanswered. We do not know the full safety profile of the combination pill nor do we know what to do in the advent of an adverse reaction. It may be difficult to pinpoint specific side-effects to specific component drug. Tailoring the dosage of component drugs will also pose a challenge. These are also fears of the stability of component drugs since Ramipril and Aspirin need to be stored at different pH, whilst the Thiazide may hydrolyse other components.

A large clinical trial with key endpoints and longer follow-up will be needed to assess the true feasibility of the Polypill. In addition, we need to ensure the message of a healthly lifestyle – i.e cigarette smoking cessation, regular physicical activity and an appropriate diet – remains the priority and global message, not the subsititute with a pill.

|

Reference List

(1) World Health Organization;Cardiovascular disease statistics (online 2008) http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/index.html. 2009.

(2) World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2005. Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment. Geneva: WHO, 2005. 2009.

(3) Reddy KS, Shah B Varghese C Ramadoss A. Responding to the challenge of chronic diseases in India. Lancet 2005;366:1744 -9. 2009.

(4) Reddy KS. Cardiovascular disease in non-Western countries. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2438–40. 2009.

(5) Reddy KS, India Wakes Up to the Threat of Cardiovascular Diseases Public Health Foundation of India New Delhi, India. JACC Vol. 50, No. 14, 2007 October 2,:1370–2. 2009.

(6) Ginés Sanz* and Valentin Fuster. Fixed-dose combination therapy and secondarycardiovascular prevention: rationale, selection of drugs and target population. 2009.

(7) Wald NJ, Law MR. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80%. BMJ 2003 June 28;326(7404):1419.

(8) Yusuf S, Hawken S et all. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study: The Lancet, Volume 364, Issue 9438, Pages 937 - 952, 11 September 2004. 2009.

(9) Chiuve SE et al. Healthy lifestyle factors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease among men: benefits among users and nonusers of lipidlowering and antihypertensive medications. Circulation (2006) 114: 160-167. 2009.

(10) Kotseva K et al.(2001). Clinical reality of coronary prevention guidelines: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I and II in nine countries. Lancet 357: 995-1001. 2009.

(11) Kristensen SD et al.(2007). Highlights of the 2007 scientific sessions of the European Society of Cardiology Vienna, Austria, September 1-5, 2007. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 2421-2430. 2009.

(12) Granger CB et al.(2003). Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med 163: 2345-2353. 2009.

(13) Mendis S et al.(2005). WHO study on prevention of recurrences of myocardial infarction and stroke (WHOPREMISE).

Bull World Health Organ 83: 820-829. 2009.

(14) Danchin N et al.(2005). Impact of combined secondary prevention therapy after myocardial infarction: data from a nationwide French registry. Am Heart J 150:

1147-1153. 2009.

(15) Ho PM et al.(2006). Impact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 166: 1842-1847. 2009.

(16) Haynes RB et al.(1996). Systematic review of randomised trials of interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Lancet 348:383-386. 2009.

(17) Bosworth HB (2006). Medication treatment adherence. In Patient Treatment Adherence, 147-194 (Eds Bosworth et al.) New York: Routledge. 2009.

(18) Bangalore S et al.(2007). Fixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysis.Am J Med 120: 713-719. 2009.

(19) Graziano TA et al.(2006). Cardiovascular disease prevention with a multidrug regimen in the developing world: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet 368: 679-686. 2009.

(20) Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2003 June 28;326(7404):1423.

(21) Lewington S et al.(2007). Blood cholesterol andvascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 370: 1829-1839. 2009.

(22) Ridker PM, Danielson E Fonseca FA et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2195–207. 2009.

(23) Dagenais GR et al.(2006). Angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitors in stable vascular disease without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure: a combined analysis of three trials. Lancet 368: 581-588. 2009.

(24) Danchin et al.(2006). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with coronary artery disease and absence of heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction: an overview of long-term randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 166: 787-796. 2009.

(25) Law M R, et al. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of

cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the

context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies.

BMJ 2009 338: b1665

(26) Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration (2002) Collaborativemeta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 324: 71-86. 2009.

(27) Yusuf S et al.(1985). Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 27: 335-371. 2009.

(28) Effects of a polypill (Polycap) on risk factors in middle-aged individuals without cardiovascular disease (TIPS): a phase II, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet 2009.

|